Released prisoners routinely face insurmountable odds when they try to get a good job and lead a better life even decades after the state says they have paid their debt to society.

It’s what’s known as the “sentence after the sentence” and former inmates aren’t the only ones who pay a steep price for permanent punishments, reformers say. In Illinois alone, more than 1,000 laws bar employment for returning felons. As a result, they say, employers lose out on productive employees eager to turn their lives around and society pays a multi-generational price for unforgiving policies.

That’s why activists at the Clean Slate Illinois and the Illinois Coalition to End Permanent Punishments and others are working to expunge records that create permanent barriers to housing, employment, education, and more.

It has proven to be an uphill battle, said the Rev. Dwight Ford, executive director of Rock Island’s Project NOW. He urges Quad Citians to ask themselves this critical question: “Do you believe someone can actually pay for their crime and be done or do you have to punish them forever?”

The latter is the consequence of a system marred by overcharging, over-sentencing and mandatory minimums. Rev. Ford said, “There are people who have been charged with murder who have never touched a weapon. They were standing next to somebody who did. I don’t think that’s the same.”

The system also relies heavily on winning plea deals from defendants – innocent or not – by overcharging them in the first place. “It’s really not the system that we signed up for,” he said.

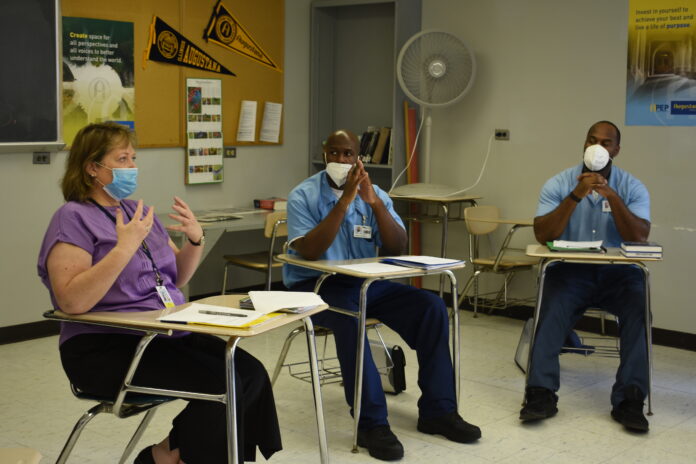

Take David Staples, the Augustana Prison Education Program graduate set to begin graduate school at Western Illinois University. He spent 29 years in prison for a murder that evidence collected by the Illinois Innocence Project shows he did not commit. Unless cleared, his record will keep him from being licensed as a counselor.

“Mr. Staples is a quality human being; brilliant, thoughtful, considerate, gracious and his case is an example of how justice can be skewed. It can be tilted in one direction and it can be awfully unfair,” Rev. Ford said. And he is “just one of many.”

Sharon Varallo, executive director of APEP, knows that well. “I know the ripple effects of incarceration on people and it is absolutely insane,” she said. That includes people like Mr. Staples and the 10% of inmates believed to be sitting on death row for crimes they did not commit.

Ms. Varallo experienced that firsthand when her daughter was wrongfully accused of a serious crime. Because her family could put the money together to hire a lawyer she was freed.

“Frankly, at first I was really interested in innocence because my daughter was accused. But I quickly got to be less interested in innocence because what I see is imperfect people, like everybody,” she said.

That population is made up, in large part, by poor, undereducated people who will re-enter society with challenges from which they can never recover.

”It is a crime that a person can pay their debt back to society, but in the public school system, they cannot even put warmed-over mashed potatoes on a lunchroom tray in a cafeteria,” Rev. Ford said. “You cannot work anywhere. And that felony can be 25 years old.”

The impact stretches across decades. “Most of the people coming out of incarceration have children,” Rev. Ford explained. “So we are contributing as a society to almost three generations of destabilization, and for the people that like to count numbers and beans and figure out where the dollars are going, it is far more expensive for this country to have to pay for everything it takes to keep a person incarcerated or under a permanent punishment.”

To see who is being impacted, Rev. Ford said search YouTube, watch Ted Talks by those who were incarcerated and talk to former prisoners in the community.

That population “is not who people think it is,” he said.

“I’m not telling you to hire them because they need a job. I’m telling you to hire them because it’s good for your business,” he added.

“These folks have been hungry and waiting to prove that they‘re different from their last conviction. They’re trying to take care of their family. They’re trying to make amends with their loved ones. They need this and you need them.”

He also challenged cities to help lead the charge, he said, pointing to the decision by the Kewanee, Illinois, City Council to allow felons to work in the city’s public works department.

It just makes sense, he said, because Department of Correction detainees can pick up trash and do other jobs for municipalities. But “as soon as they cross the line and come out of there they can’t get a job doing the same thing.”